From maintainer(s) to maintainer(s)

(Harley Lara, Jun 2025)

This is a note to myself, to my colleagues and to the future of the EOLab System.

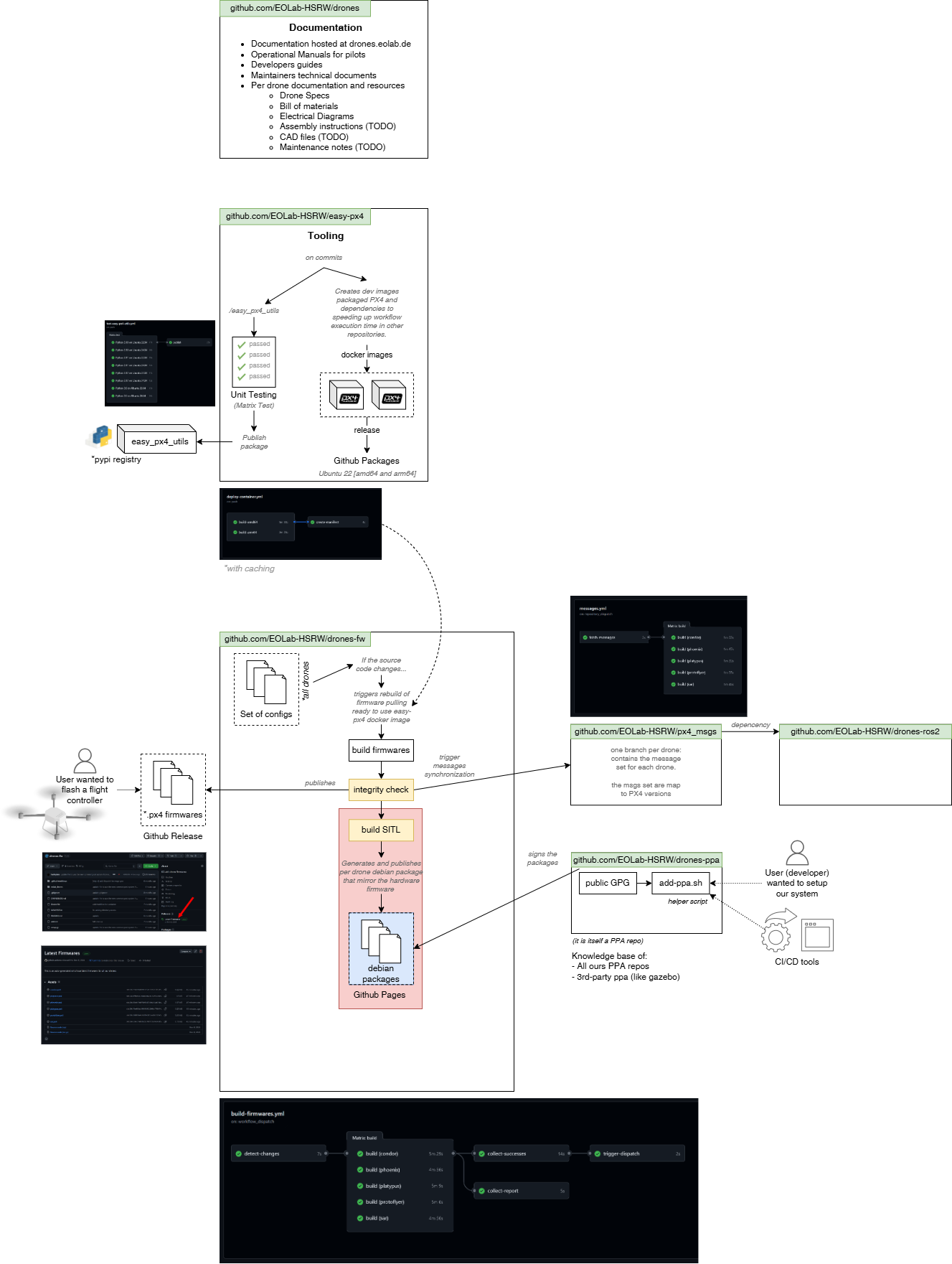

Infrastructure Overview

This section presents all the pieces of the EOLab Drone System infrastructure. Note that it is not intended to provide detailed insights into the motivations behind the system's design decisions. For a complete rationale and a detailed walkthrough of why the system is structured the way it is, see the Design Docs section.

List of the CORE repositories that the maintainer has to take responsibility for:

| Repo | Status | Short description |

|---|---|---|

drones | Active | Documentation (this website) and drone assets |

easy-px4 | Active | Core tool in our pipeline for firmware build automation |

drones-fw | Active | |

drones-ros2 | Active | Core ros2 package to interface the firmware from companion computer |

px4_msgs | Active | Sync px4_msgs. Always in sync with px4-firmware version per drone |

drones-rc | Active | Collection of configuration files for our Radio Controllers (RC) |

drones-ppa | Active | Debian package public signature and ppa repo |

Hardware repos:

| Repo | Status | Short description |

|---|---|---|

dronebridge-radio | Active | Our MAVLink telemetry radio with mesh support |

NanoCore-525 | Active | A reference design of a DC-DC power supply with 5V 25W output power |

sar-drone | Active |

Software tools to enable our drones:

| Repo | Status | Short description |

|---|---|---|

PlaneSweepLib | Active | |

OpenREALM | Active | |

OpenREALM-ros2 | Active |

Historical Background

By 2020 the Drone Lab (Drohnenlabor) at HSRW was already established with some previous projects involving drones, such as Smart Inspectors (INTERREG IV A) and SPECTORS (INTERREG Va, 2016-2020) to mention a few, and there was cool people working with drones at HSRW like Moritz Prüm, Winfried Rijssenbeek, Marcel Dogotari, Rolf Becker and more (see SPECTORS Team).

Then, COVID slowed down activities until the beginning of 2024, when the Emergency Drone (Interreg VI A) project began development, and Harley joined as an official developer in the project. At the time, the EOLab/Drone Lab team was flying often with DJI drones and occasionally with self-built drones (from past projects) for demonstrations. Around May 2024, Prof. B. Rolf asked Harley to synthesize a list of the lab’s drones and robots at the time, and it became apparent how many systems existed, some of them unused for years, without documention or reference manual for operation.

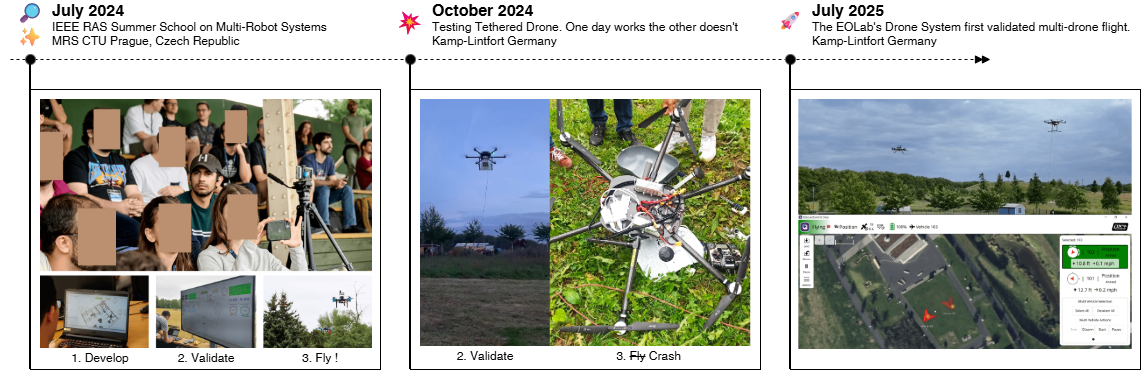

In July 2024, through the Emergency Drone project and the support of people involved, Harley had the opportunity to attend the IEEE RAS Summer School on Multi-Robot Systems, hosted in Prague, Czech Republic and organized by the Multi-Robot Systems (MRS) group at CTU, one of the leading multi-robot drone research teams.

Harley: I was genuinely amazed by the overall infrastructure of the development team and the MRS UAV System. We were assigned a task and iterated our implementation in simulation, and on the last day of the summer school they ran our implementation to validate that we did not violate any physical constraints. If we passed all checks (we did), they deployed our implementation to the physical system in the field. They did the same—live—for 30+ teams that day. It was the first time I saw “it works in simulation, it also works in reality” in a way that felt so tangible and achievable.

That experience planted the idea of possibly doing something similar for the lab’s catalog of drones. However, it was clearly a titanic task to document all systems and unify them into a more reproducible, testable, and workable umbrella system for development. This effort could have shifted focus away from the main project—Emergency Drone—and, given the time constraints and the need to meet deadlines within the Emergency Drone work packages, the risk of losing focus was considered too high. As a result, the idea of creating such a development environment did not take off, and all drone-related work remained focused exclusively on the Emergency Drone platforms, with limited to no attention given to older legacy platforms in the lab.

In October 2024, the only tethered test platform in the Emergency Drone project crashed during a demonstration with project partners. The demonstration consisted of showcasing the use of a tethered power supply combined with batteries, and how unplugging the tether from the grid would not affect the drone while flying. The demonstration had been tested multiple times beforehand, all successfully, including a test the day before to ensure everything was ready to be packed for the next day. However, during the live demonstration, at the moment the drone was unplugged from the grid, an electrical failure in the BEC affected the flight controller. The drone then fell from approximately 10 meters above the ground and crashed into the ground.

Harley: There was the classic loud, low-frequency buzzing sound of a drone of that size (15 kg payload), and suddenly it went silent, ending the moment with the sound of the drone crashing into the ground. I felt a mix of rage, frustration, and sadness. Thankfully, nobody was hurt, and nothing was damaged other than the drone.

The crash ignited the motivation to rebuild the system from the ground up and take the opportunity to enable all drones in the lab to become active development platforms. Then, the EOLab Drone System was born. The crashed drone got the name of EOLab Phoenix.